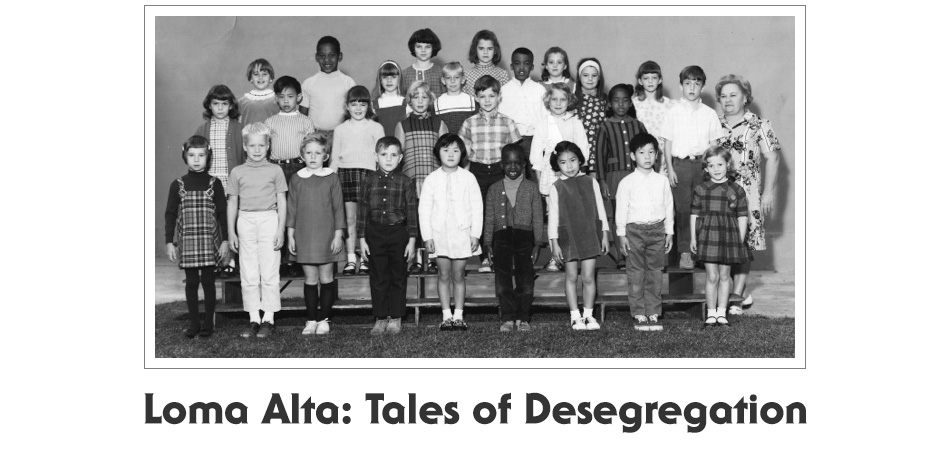

In 2015 I received a grant from the Pasadena Arts & Culture Commission and the City of Pasadena Cultural Affairs Division to write memoir pieces about my years at Loma Alta Elementary School in Altadena. This was during the time that Pasadena Unified School District—the first district on the West Coast—was federally mandated to desegregate in 1970. Select pieces of the project were presented with essays written by two guest contributors—my classmate, Abby Delman, and a former John Muir High School student, Meredeth Maxwell. The program generated much discussion, revealing that this complicated and sensitive time period has yet to be fully processed, more than forty-five years later.

Thanks for reading.

Naomi Hirahara

Essays

The Clan

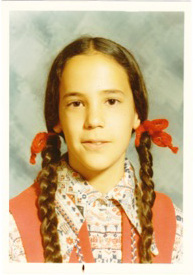

By Naomi Hirahara

There were four of us—Chantel, Latoya, Anna, and me, Naomi.

Taking the first letter of our first names, we called ourselves the Clan.

One day Latoya came to school and told us her father said clan was a bad word. My heart sank and I was worried. It had taken us a long time to think of that name.

We went to the dictionary and looked up clan. One of the definitions said, “A group of people with interests in common; clique; set.” That didn’t sound bad to me. Then we found out later Latoya’s dad was talking about the Klan, spelled with a capital K. The Klan had done very bad things to black and Jewish people. I wasn’t either of those people. My mother was from Japan and I was born in California. I wasn’t Jewish like Anna or black like Chantel and Latoya. But I thought the Klan wouldn’t like me very much, either.

We decided to keep the name Clan, although I don’t think the rest of the group really cared what the group’s name was We went to school with big, acrylic bags with handles and if anyone gave us any problems, we would swing them far and wide.

Chantel was light-skinned with perfectly coiffed hair, usually in two puffy braids. She lived up the block from our home on McNally Street. I went to her house once when she was waiting for the iron to heat up to straighten her hair. Even though we were in fifth grade, she was already wearing a bra—a real one with actual cups. I, on the other hand, wore only a white undershirt beneath my tops. Chantel’s voice was deepest among ours, and she moved and acted with confidence. She knew who she was.

Chantel usually paired off with Latoya while I spent more time with Anna. Maybe Chantel and Latoya had more things in common. Latoya had the biggest eyes; they looked like Bambi’s. She was probably the prettiest out of all of us. She was skinny with bony arms and liked to surprise us with her hairstyles. One day she combed her hair out in an Afro that seemed to be a foot high.

Anna was on the quiet side, but maybe not as quiet as me. She came to Loma Alta on a yellow bus. I was impressed because it was such a grown-up thing to do. At the time, I wasn’t quite sure who came on a bus and who didn’t. Since I was in kindergarten, I always walked to school by myself on Loma Alta Drive on a dirt path along the street with no sidewalks. The mountains, which seemed to glow purple sometimes, was on my left side as I made my trek to school.

Anna had some older brothers and sisters and I loved to go to her house, which was a lot nicer than mine. While my bedroom had this old linoleum with nursery rhymes printed on it, Anna’s had a nice, soft carpet with a full closet with doors that folded in and out. I especially like her dad because he cracked jokes and told me to try eating peanut butter sandwiches with bacon. It sounded really horrible, but I tried it and it tasted good.

I was always trying to get everyone together, as if we belonged to a special club. I made a booklet for the club with my version of Snoopy on the cover. I was always making books out of construction paper, which I punched holes in and connected with metal fasteners. Maybe it’s because I was the only kid in the family for so long. Somehow belonging to a group of girls felt so good to me. One day, a girl in our class, Tonya, a white girl with straight honey-colored hair, came up to us and said she wanted to join our group. Tonya was nice enough. She didn’t smile that easily, but always wore neat polyester sets of matching top and skirt. She had a mole on her cheek that somehow made her look more sophisticated than her nine years.

We deliberated about Tonya by the concrete steps. We didn’t talk for long. We decided not to let her in. The Clan was only for us four.

Around that time, my little brother was born. Before my parents left for the hospital, they said they were going to name him Martin or Peter. I didn’t like either one of those names. Martin sounded like Martian and My Favorite Martian was a popular TV show back then. I couldn’t imagine a baby with antennas. And Peter made me think of Peter, Peter, Pumpkin Eater. But when my mom came back with my brother wrapped up tight in a blanket, she and my dad announced his name was James. We would call him Jimmy.

Things started to change after Jimmy came. Even though I was barely nine, I was in charge of watching him while my parents looked for a new place to live. Then my parents announced we were going to move away to a place two towns over—South Pasadena. Even though it wasn’t that far, it seemed like worlds away from Altadena.

Anna said we would be reunited again. That we would all go to Pasadena City College after we graduated from high school. We promised each other we would. But somewhere in the back of my mind, I knew I probably wouldn’t see them again.

Petite Prejudice

By Abby Delman

I was beginning fourth grade when desegregation began in the Pasadena Unified School District. We lived on the eastern margin of the district in Sierra Madre, a town made up mostly of middle class and upper-middle class white people. High schoolers attended nearby Pasadena High School, where children from across town—and often less fortunate means—were bused in. I was bused to Loma Alta Elementary School, about forty-five minutes each way. I was torn from my three good friends who had attended Sierra Madre Elementary School with me. They were shipped to Altadena Elementary School, but I lived north of Grandview Avenue, so I was shipped to another destination. Even though we all ended up at Pasadena High, the five years of being apart forever distanced me from them.

Where my siblings encountered racism and violence from displaced high school classmates, I witnessed hatred, not from other elementary school students but from my fourth grade teacher, a small woman with translucent skin and white hair. Two instances stand out for me. One involved a boy who sat at the same table with me. He was a class clown and he was charming and I had a crush on him. The other involved the biggest girl in class, whose handwriting was so small you had to squint to read it. Both children were very dark-skinned. I remember being shocked and appalled when the teacher threw a hardcover textbook at the boy because he was being silly. Her face got red and she looked out of control. Add disheveled hair and fight postures to the picture, and that’s what she looked like when she engaged the big girl in a fist fight and wrestling match in the classroom. The art supplies were flying everywhere. The teacher ended up restraining the student. I felt terrible for the student and scared about the future in that class.

Growing up with parents who embraced differences and were in support of desegregation, and older siblings who were facing discrimination, violence, and racial tension at their school, I was now beginning to form my own ideas. It seemed to me young children were accepting of one another and got along fine when tossed together, but it might be too late for teenagers and adults to get along if they had already learned to be prejudiced.

Fighting for civil rights in the fifties and educational equality in the sixties, many US citizens attempted to reverse the racism of the past by elevating the perceived status of minorities relative to whites. This was evident in my early interactions. One friend of mine was biracial and was embarrassed by her white parent. I witnessed a friend’s older brother being scolded by his mother for wearing a dark color because it made his skin look lighter. And when a classmate of mine saw my mother and me in the school office, he whispered his condolences to me and admitted his mother was white, too.

I remember the friends I made at Loma Alta fondly. A group of us called ourselves the Four Musketeers—two black girls, one Japanese girl, and me, the white one. We enjoyed our time together at school. It was hard to get together to play after school and on the weekends, though, because we lived so far away from one another. I remember spending the night at another friend’s house. I was in awe of her big sisters, who performed cheer routines in the living room. We had popcorn for dinner. We all slept in one bed, the three sisters and me. They were black and they were poor and they shared what they had with me. I was awake much of that night because I was hungry and trying to not fall off the side of the bed.

The desegregation effort was a noble one, making access to resources more equitable across all children from all neighborhoods. I don’t believe the goal was to encourage cross-class relationships, understanding, and tolerance, but it did for me. The policymakers were focused on equal exposure to learning resources. The way they chose to do this—by moving people around—made us more accessible to one another. Perhaps we are the best resources of all.

Abby Delman lives in Pasadena and is a psychology professor at Pasadena City College. After graduating from Pasadena High School, she attended the University of California at Irvine, where she earned a bachelor of arts in social ecology. She followed that degree with a master of arts in psychology from California State University, Los Angeles. She is married to Jey Giuliano, and they have an adult daughter named Roxann.

Hot Pants

By Naomi Hirahara

I’m not sure how the new school dress code was told to us, only that the news spread fast on the playground: No hot pants allowed.

I didn’t wear hot pants. I might have owned a pair or two, but they were accidental hot pants, a size too small that made them creep up my meaty thighs. But a pair of fluorescent colored ones on purpose? No, this code didn’t affect me, the daughter of a Japanese woman who was always impeccably dressed.

It did affect Rickie. She had bangs that still had the curl of her roller. She had a face that meant business. And she wore hot pants.

Her pants were pinkish, not of a shade of rose but drops of blood that first emerge from a cut. I, on the other hand, wore stuffy dresses imported from Japan or outfits my mother made from Simplicity patterns.

Rickie strutted on the playground in those hot pants. Her dark brown legs were lean and defined Sometimes she tied her blouse up in a knot so her middle was showing. I had gone to kindergarten with Rochelle and she was different back then. It was like she had been holding everything in and it all came out in fifth grade.

I actually kind of knew what she felt like. I didn’t like my fifth-grade teacher. We never saw eye to eye on anything. One of my favorite teachers was Mrs. Knudsen, who taught fourth grade. She thought I was a literary genius. Really, she did. When we got spelling words, instead of stringing them into sentences, I made them into a story. It didn’t matter how unrelated all the words were.

But when I went from Mrs. Knudsen to the next grade, something happened inside of me. We also moved from class to class for different subjects and it was hard to believe any adult really cared about me.

So I acted up. I talked back to my homeroom teacher. She wasn’t nice and I thought she was ugly. I don’t know if she liked any of us kids. I know I didn’t like her.

My mom came home from a parent-teacher conference all upset. She was used to having good reports from my teachers, teachers like Mrs. Knudsen. “I hope Naomi isn’t too quiet,” is what my mother had said at the conference. My fifth-grade teacher responded, “Your daughter is wild, ma’am.”

Even with this bad report, I didn’t get in that much trouble. It was if my mother was in shock about my misbehaving at school. But she had little idea what happened in the classroom and on the playground.

For instance, our group, the Clan, carried around acrylic bags like weapons around the school. One of our classmates was Charlie, literally one of the whitest boys at school. He had peroxide-blond hair and pinkish skin and wrinkly eyelids. There was nothing wrong with him; I might have even had a crush on him. But one day, out of the blue, I wanted to fight Charlie. I wanted to push him down and stomp on him. I didn’t do either, but I did swing my bag back and hit him as hard as I could. He looked at me, blinking his papery eyelids, measuring why I had done what I did. Before I knew it, he pushed me and then a tornado of children circled us, yelling, “Fight, fight, fight.”

Before anything more could happen, the vice principal came down the schoolyard steps and everyone scattered, including Charlie and me. I was in a fight for barely five seconds. During those five seconds, everyone was looking at me. I was on stage on the concrete. I didn’t feel proud, but I wasn’t embarrassed. I should have felt bad because Charlie had done nothing to deserve what I did to him. It was my way of feeling like I was wearing hot pants, that I was dangerous and formidable.

That I meant business, too.

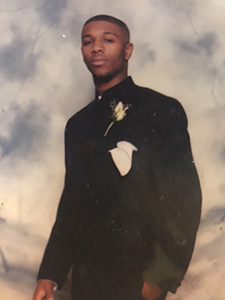

First Day of High School

By Meredeth Maxwell

Growing up in Pasadena was interesting and often volatile, especially in the ’90s. Seeing a friend bedaubed in red or blue, with a few Latino friends staking a claim to a gang by wearing khaki suits, was a common occurrence. I believe my latchkey status protected me from getting in trouble. Mom was no dummy, but she knew she could only protect me for so long. As a result, my life was void of the “true friend,” and consisted mainly of acquaintances until middle school.

It was hard to maintain friendships safeguarded behind double-latched doors, security bars on windows, the occasional babysitter, and Spinks. Spinks had a boisterous bark that could be heard around the block. Even if she wasn’t vicious, she sure looked the part.

I absolutely hated being indoors all day, watching my neighborhood pals running about, probably up to no good. When the sun fell, however, and the sounds of the night overwhelmed my senses, I completely understood why I was “locked up.” Mom would rather know where I was than ponder the alternatives, but we both realized one day soon the locks would have to come off and the doors would swing wide open.

I remember it like it was yesterday, that winding alarm clock blasting my ears at six a.m. sharp. I wanted to jump up, but the twisting feeling in my stomach kept me pinned to my bed. My thoughts were running through a labyrinth, jumbled with crazy thoughts of my newfound freedom, the potential, the friends, the bullies, and the journey. Yes, I always thought of the bullies. I was a bully magnet. I suppose it was a result of always being inside, new or misunderstood by the wannabe alpha male. Nonetheless today was a new day, thirteen years young embarking on my first day of high school.

Once I had gathered the strength to jump out of bed, I marveled at my first-day outfit, meticulously laid out over my top bunk. We didn’t have much, but Mom always found a way to provide a few bucks for school shopping. The outfit was a finely pressed pair of 501 Levis, with a Vano-startched crease, sharp enough to cut paper. I deliberated between the K-Swiss shoes and the steel-toe boots, but the boots seemed to be calling my name. My short-sleeve Eddie Bauer shirt was pure white, coupled with a new Jansport backpack to send me off.

Before I could get too excited, Mom’s firm morning voice rattled through the house reminding me of my morning chores. I couldn’t leave the house soon enough. Minutes later, after a refreshing shower, the radiant smell in the kitchen drew me near as I finished looping my belt through my oversized jeans. My mom, with her wig halfway on her head, had me salivating at the simmering pot of cabbage, sausage, and potatoes. Her six-foot-one frame blocked the pot, but I knew the smell all too well. She placed a nice-sized portion of food on the small kitchen table, along with a set of two keys and a ten-dollar bill. We were not a touchy-feely kind of family, but “having you prepared” was her way of showing love.

We went over the routine several times. I knew I was far enough to take the bus, yet close enough to walk. Fortunately, I could navigate Pasadena very well, and I decided to walk. Before I could head out the door, she left me with two requests. The first: no headphones while walking on the street. The second: start the car. The first request I knew I’d never honor; once I was out of sight, those headphones would be blaring in my ears. The car was something I reveled in. I was too young to drive but the car-starting routine fueled my hopes, plus it saved my mom time as she was often running late. The routine, as I recall, was: insert the key, hit the gas twice, turn the ignition off, then back on, and rapidly press the gas pedal until the engine turned over, which fed the clean air with gray and black exhaust from the rusted tailpipes of our ’88 Cadillac Brougham.

My trek down Morada Place that day was unusually eerie. The warm morning filled with sounds of birds and swiftly moving cars suddenly felt cold and silent. I put on my forbidden headphones, trying to ignore the feeling. As I approached the corner, I understood that the cold and silent feeling was my intuition warning me of what was to come.

I didn’t take another step, doing my best to play possum. The middle of the sidewalk at this moment was not a good place to be. My heart was pounding my ears, and the sweat was beading up on my forehead. The scene was ridiculous. My nervous eyes gazed at dozens of gang members from a local Crip gang occupying a grassy knoll. I couldn’t even see one blade of grass; there were so many of them. It was strange because I’d taken that route dozens of times and I’d never seen them there before. It was like they knew it was the first day of school and they were scouting for recruits. The choice was simple—turn around as quickly and quietly as possible.

I did an about-face and dashed toward the nearest bus stop. Catching my breath at the corner, with the bus stop in the distance, I wondered if the bus would truly be a better option. Before Metro, we had the RTD, or as we called it, the Rough Tough and Dangerous. The bus pulled up about ten minutes later. It was a sight to see. Kids from various neighborhoods gathered together in the rear, and the responsible adults in front. As a habit, I always sat in the front or near the door. Today the bus was full and only one space was left right behind the driver. I happily took it.

About twenty minutes later, the bus came to a squeaking stop directly in front of John Muir High School. I took in the sights. The first day was absolute chaos—kids and parents everywhere! I couldn’t help but think how much this massive building looked like a prison. The gates, school security, and police slowly patrolling the area all added to the décor. My thoughts were interrupted when the bus driver yelled out the next stop.

Before the driver finished his sentence, Latino gang members bombarded the front of the bus. I grabbed my bag and looked toward the rear door. This can’t be happening again, I thought. The rear of the bus was jammed by the Latino gang. I could hear my heart and feel the beads of sweat dripping from my forehead again. Time felt frozen. I looked back to the front of the bus, and there stood a large man with a switchblade pointed at me. Deaf due to my impending doom, I read his lips loud and clear: “Get off the bus!” I didn’t hesitate, but as I passed him, I realized who this young man was. He wasn’t a friend but an acquaintance. Ernesto, the son of a woman who used to babysit me, decided to let me live another day. We had last seen each other nearly six years prior, and it was this acquaintance rather than a friend who decided to have mercy on me. As I took my last step off the bus, I turned back. The bus had broken out into a complete riot. Still in shock, I walked into the parking lot, pulled my class schedule from my pocket, and headed to my first class.

After completing a B.S. in Broadcast Journalism with a M.A. in Mass Communications at the University of Wyoming, Meredeth Maxwell has been a jack of all trades. He has been a grassroots organizer, distribution manager, real estate broker, licensed real estate appraiser and small business owner/operator. He was a Partnership Specialist Team Leader of the 2010 decennial Census. For the past six years, he and his wife have had an appraisal business serving the Pasadena region.