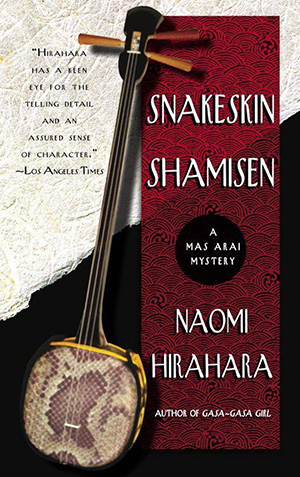

Bantam Dell/Delta trade paperback and ebook, April 2006

Winner of the 2007 Edgar Allan Poe Award in the category of Best Paperback Original

Few things get curmudgeonly Japanese American gardener Mas Arai more excited than gambling, so when he hears about a pal’s half-a-million dollar win—from a novelty slot machine!—he’s torn between admiration and derision. Bu the stakes suddenly get higher when the winner is found stabbed to death; only a battered snakeskin shamisen (a traditional Okinawan musical instrument) may hold a clue to the killer’s identity. Mas reluctantly agrees to follow the trail left by the shamisen—and soon uncovers a world of secrets and deceptions that stretches from the streets of L.A. to the islands of Okinawa.

“Hirahara’s well-plotted, wholesome whodunit offers a unique look at L.A.’s Japanese-American community, with enough twists and local flavor to keep you guessing till the end.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“The cadence of the book is all music and past rhythm; what will be in store for Mas next? I can’t wait.”

—Sarah Weinman, Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind website

City of Duarte’s 2007 One Town, One Book, selection

2007 Anthony Award nominee

Excerpt:

“Once we meet and talk, we are brothers and sisters.”

–Okinawan proverb

“The nail that sticks up will be hammered down.”

–Japanese proverb

Chapter One

Mas Arai didn’t think much of slot machines, not to mention one with a fake can of Spam mounted on top of it. Mas was a poker and blackjack man, and he had been for most of his seventy-odd years. Slots were for suckers. For heavy hakujin women in oversized T-shirts and silly earrings. And as far as he was concerned, Spam was strictly for eating—a fat, shimmering slice resting on a rectangle of sticky rice and tied together with a band of nori, dried seaweed. That’s how most of the Japanese he knew in L.A. ate it.

His late wife, Chizuko, hadn’t been a fan. She was straight from Japan, while Mas had bounced back and forth from row crops in his native California to the rice fields of Hiroshima. Chizuko had disapproved of Spam, and instead attempted to push natto—fermented soybeans, sticky as melted glue and rancid smelling as a baby’s behind—onto their unsuspecting neighbors. Only Mrs. Jones, a large black woman with a middle as wide as one of the tires on Mas’s Ford gardening truck, had taken up Chizuko’s offer. After she’d opened her mouth wide, placing the web of natto on her tongue and swallowing the sticky and stinky beans, Mas had half-expected her to rise from their kitchen table and head for the bathroom. But instead she’d smiled sweetly as if holding on to a secret. “Like okra,” she’d said. “Only chewier.”

Mas was more of a Spam man, with some limits, of course. Spam was perfectly acceptable at potlucks of the Americanized Japanese, in particular the second generation, the Nisei, and their children, the Sansei. Mas could live with Spam being served at the coffee shop of the California Club, a favorite casino choice of Nisei families, Hawaii-born gamblers, and gardeners like Mas. Hell, he would be first in line to order Spam, eggs, and rice for breakfast or a couple of Spam sushi, referred to as Spam musubi, as a midnight snack. But once he left the confines of the coffee shop, he just wanted to fix his eyes on the clean surface of green felt tables.

Yet to get to those dollar blackjack and poker games, Mas always had to make his way through rows of slot machines. In recent years, it had only gotten worse. Instead of the standard slots, with cherries and 7s, these new machines joined the video age and took their themes from old television and game shows. Others looked more like children’s games, with jumping frogs and Chinese takeout boxes and silly cartoon sounds. Too much noise. Mas just gritted down on his dentures and shook his head as he passed by.

But when he first laid eyes on a Spam slot machine, he knew that the gaming industry had gone one step too far. First it was that ridiculous lit-up giant Spam can positioned on top of the machine like an askew crown. Then there were the multiple video images of people eating and serving Spam, and then Spam itself. What did any of that have to do with gambling?

Those thoughts returned to Mas as he sat in his fake leather easy chair in his own living room after a meal of rotisserie chicken from the local discount warehouse store. He was reading the L.A. Japanese daily newspaper, The Rafu Shimpo, as he did every evening, when he saw it—a quarter-page photo of a Spam slot machine on page three. And that wasn’t the worst of it: two Sansei men were clutching the slot machine as if it were a Vegas showgirl. They had leis around their necks and glassy looks on their faces. Drunk as skunks, thought Mas. He adjusted his reading glasses. One of the men in the photo, a guy with long graying hair pulled back in a ponytail, looked familiar. No, couldn’t be. Mas turned on the light beside the easy chair, pounding excess dust from the lampshade. There was no doubt now; it was his best lawyer friend—well, only lawyer friend—G. I. Hasuike. Beside him was a thick-chested Sansei man in a tight T-shirt. He had a mustache and sideburns. He looked like any other Japanese American man of a certain era. The type to hang out in smoky bowling alleys and pool halls. In the man’s left hand was a cardboard rectangle, a giant check from the casino. Mas carefully counted the zeros. Five of them, all behind a number 5.

“Sonafugun,” Mas muttered. Half a million dollars. He read the caption underneath the photo. “Randy Yamashiro, left, celebrates winning $500,000 in the Spam Slot Machine Sweepstakes at the California Club casino in Las Vegas with friend George Hasuike.” Mas groaned. Now every Japanese fool, every single aho, would be making their way to the California Club for a try on the Spam slot machine. Any child, or even a monkey, could stuff coins into a slot. It didn’t require the guts and smarts necessary for card games. It wasn’t fair and it wasn’t respectable. But then again, $500,000 could buy its share of respect.

There was a brief story underneath the photo and caption:

Randy Yamashiro, a resident of Hawaii, credits George Hasuike as his “good-luck charm.” Yamashiro, who is visiting the mainland from Oahu, announced that he will be holding a luncheon in Torrance, CA, in Hasuike’s honor later this week. The two men were in Las Vegas for a reunion of Asian American Vietnam War veterans.

Mas knew that he should be impressed with Yamashiro’s generosity, but instead it made him sick. Going to rub our noses into it, thought Mas. The last thing he would do was go to any meal paid for by a winner of a game based on a food product.

Mas’s best friend, Haruo Mukai, of course, was of another opinion. Haruo, like Mas, had escaped from the ravages of the Bomb in 1945. Mas returned to America, his birthplace, physically intact, whereas Haruo had left his dead eye behind in Hiroshima. Haruo’s good eye was as good as, if not better than, a pair of Mas’s eyeballs; he saw things that Mas had a hard time seeing. Like their obligation to go to that luncheon. Haruo had received a personal invitation—Mas would have, too, if he’d bothered to get an answering machine.

“We gotsu a go, Mas,” Haruo insisted over the phone. It was close to eight, the time Haruo usually went to bed before working the graveyard shift at the flower market in downtown Los Angeles.

“I don’t have to do nutin’,” Mas replied. Sitting at home seemed like a more appealing option.

“Osewaninatta. G. I. the one who help youzu out wiz a ton of legal problems, rememba?”

Like a typical Japanese, Mas thought, Haruo would pull out that card. Osewaninatta, Japanese would say to each other. I am in your debt. You’ve helped me out, and I owe you, big-time.

“Get you, Mari, out of more jams than you can count,” Haruo kept going.

Mari was Mas’s daughter in New York City, and Mas didn’t appreciate Haruo using her as part of his argument.

“Yah, yah, yah,” Mas said quickly, not wanting to be reminded of past troubles. “Orai, orai.”

Mas ended the call soon after that. He immediately regretted agreeing to go to the party. It was fall, a time to reassess and rescue scorched lawns and dried-out plants on his gardening route. It was a season to restrategize, not to wander twenty miles south to the coastal suburb of Torrance.

Haruo had invited Mas to go with him and his girlfriend of two years, Spoon Hayakawa. Spoon’s real name was Sutama, but Mas guessed that it could have been worse—being called “Fork,” “Knife,” or “Chopstick,” for example. Shaped like a gourd, she had long salt-and-pepper frizzy hair, which she held back with a stretchy headband. She was also a Nisei, and being an all-American gave her an easy sense of humor. Mas and Haruo, on the other hand, were Kibei Nisei, which meant born in the U.S. but raised in Japan. This duality resulted in men and women who were either sweet or sour. Haruo was sickeningly sweet, the type to hold hands with his girlfriend even when he was pushing seventy-two. That was hard to take for Mas, the classic sour, so he declined Haruo’s offer. Another invitation came from other family friends, Tug and Lil Yamada. Again, Mas passed, making up a story about needing to deliver some plants to a customer on his way to the restaurant. The last thing Mas wanted to be was a third wheel. Indeed, if he had to go, Mas would go alone.